Where does China want to be?

China, the world’s biggest emitter of carbon dioxide in 2020, pledged in September 2020 at the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly to strive for peak CO2 emissions by 2030 and work towards carbon neutrality by 2060.

What it’s been doing to get there:

China has been updating the details on how it aims to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2060:

• Limited emissions will be implemented for new pollutants by 2025, according to the Action Plan for the Treatment of New Pollutants.

• Pledges to stop financing new coal plants overseas in March 2022.

• The State Council issued the Responding to Climate Change: China’s Policies and Actions in October 2021 confirming the targets of peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality before 2060, and further sets targets to:

Lower its carbon intensity by more than 65% (previously 60-65%) by 2030 from the 2005 level.

Increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25% (up from around 20%) by 2030.

Increase the forest stock volume by six billion cubic meters (up from 4.5 billion) by 2030 from the 2005 level.

Bring its total installed capacity of wind and solar power to more than 1.2 billion kW by 2030, which is additional to previous announcements. Investments in solar power were USD4.3 billion (CNY29 billion) from January to April 2022, up by 204% from the same period in 2021.

Raise the target for new energy vehicle share from 20% to 25% by 2025.

But, as stated in the Climate Action Tracker, these policies are not enough to bring the temperature down to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. More green policies are expected from China. The China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT) estimated that to achieve net zero carbon emission by 2060, China needs to invest $21.3tr.

So far, China has put policy objectives into action with the following:

• Issued $57bn (CNY382 billion) green bonds in the first half of 2022, an increase of 202% year-on-year.

• Added another $14.9bn (CNY100bn) loan to support the clean and efficient mining, processing and utilisation of coal-powered energy by China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China.

• Increased sales of electric vehicles by 122.5% year-on-year to 2.3 million in the first half of 2022.

What’s happened since the Ukraine war

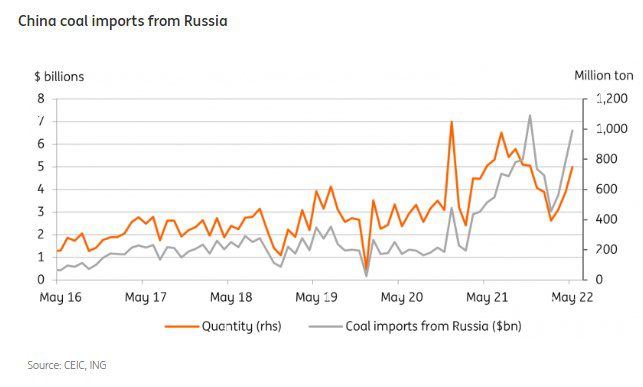

Since the start of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, China has increased its imports of coal, crude oil and natural gas from Russia.

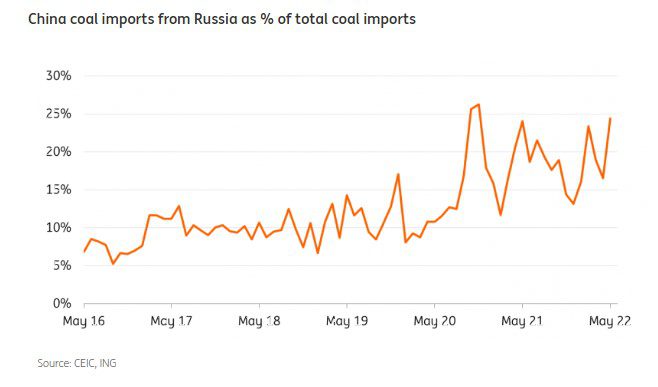

Although one-third of China’s coal imports come from Russia, Russian coal accounts for less than 1% of total China coal supply, which includes a big portion of domestic supply.

We believe that China will at least maintain this level of coal imports from Russia in 2022, as it looks to have an adequate power supply standby for economic recovery this year.

In addition, China is going to cut import tariffs for coal to zero from 1 May 2022 to 31 March 2023, which could lead to more imports of coal from Russia.

These two measures are in line with the compromise approach of moving slowly from coal to renewable energy so that the power rationing seen in 2021 will not reoccur.

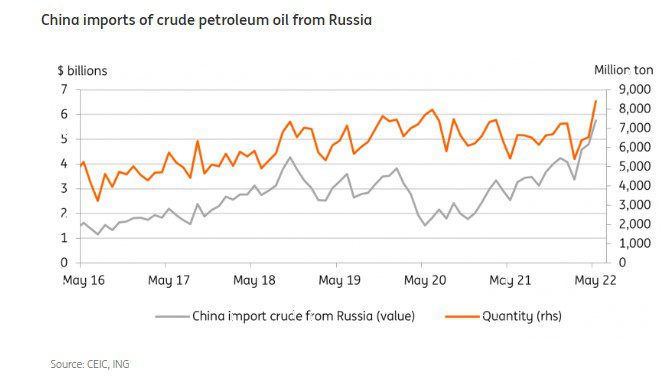

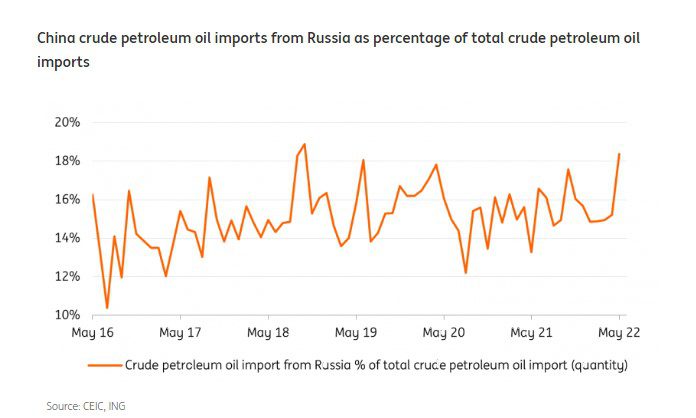

According to Chinese customs data, crude oil imports from Russia rose to more than 18% of total crude oil imports in May from 15% in April. This increase has already exceeded the previous high of 17.6% in October 2021.

This comes as Russia signs an agreement with China to supply 100 million tonnes of oil over 10 years – which extends the existing agreement – worth $80bn.

We expect Russia’s contribution to China’s crude oil imports will increase to more than 20% in 2022. This increase started in May as China imported 28% (month-on-month) more Russian crude petroleum, with the monthly import value growing at a slower pace at 20% MoM. This indicates that China bought Russian oil at a cheaper price in May. Imports from Russia should have added to strategic reserves, like imports from other economies, with total crude petroleum oil imports edging up 2.93% MoM in May. For China, Russian oil has so far not replaced oil imports from other economies.

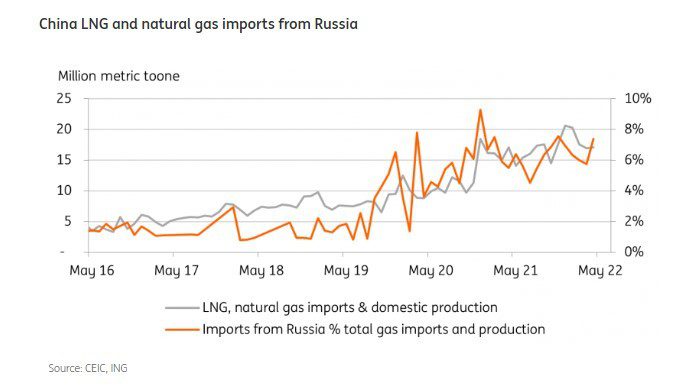

In 2021, China overtook Japan to become the world’s largest importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Russia is the third-largest supplier of LNG to China, contributing more than 9% of China’s LNG and natural gas import value in May 2022, from 12% in April, above the 5% average in 2021.

There will be even more imports of natural gas from Russia in the coming years. In February 2022, China agreed to buy 10 billion cubic meters of LNG from Russia via pipeline for 30 years. In the previous deal, Russia supplied 38 billion cubic metres of gas via pipeline until 2025, according to Reuters.

However, this does not necessarily mean that China will import less LNG from Australia and the US, which are the number one and two suppliers of LNG to China. LNG is less polluting. When China’s economic growth stabilises as lockdown measures ease, the policy-driven stimulus will fade, and by that time, coal power sources will gradually be replaced by LNG and renewable energies. China’s demand for LNG and natural gas will continue to rise.

Fast track to reducing carbon emissions didn’t work

China experimented with the pace of reducing carbon emissions, which could provide a valuable lesson to other economies that there is no fast track for reducing CO2. In 2021, some cities cut back on coal production significantly to achieve a reduction in carbon emitted from coal power. The result was electricity shortages. That incident was not caused by a lack of coal supply but rather a bid to cut carbon emissions, which ended up in power rationing.

This highlights power security as a risk when China reduces carbon emissions after 2030. To mitigate this risk, the government increased more than 350 Mt per year of coal mining capacity in the second half of last year. Although China has pledged to stop building coal-fired plants abroad, it increased coal power within China with more than 15 GW approved so far in the first half of 2022.

In 2022, domestic coal production saw a jump in February, while coal imports were also on the rise. The government wants to ensure that electricity supplies are sufficient to support the economy’s recovery after the economic damage caused by Covid lockdowns.

It seems that the progress towards meeting its carbon emission commitments is being compromised despite announcing that it will “control coal consumption rigorously” in its 14th five-year plan from 2021 to 2025. But China believes that building a clean coal power plant is a transition phase between traditional coal-powered electricity and electricity from solar and wind.

Rather than just giving up coal power, the government announced in May 2022 that it aims to move seamlessly from coal to renewable energy by upgrading 600 GW of coal power plants to increase the standby time and enable them to ensure power supplies when wind and solar are insufficient due to unfavourable weather conditions.

Summary

In short, since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, China has started to import more coal, crude petroleum oil and natural gas from Russia. This is not only a result of international politics; China also needs stable energy imports for its economic recovery. The failure to speed up CO2 reduction in 2021 has resulted in even more reliance on coal fire power to ensure the stability of the power supply. Lockdowns during March-May have cut carbon emissions, and therefore China may be able to achieve flat CO2 emissions in 2022. China is building more green infrastructure, which on the one hand helps to support economic growth, and on the other, helps it to stick to its progress of peak carbon emissions by 2030.