Since our July 28 article, the US economy has produced another confusing batch of signals. Start with the good news: Q2 GDP was revised higher, consumer sentiment moved a touch higher, Q2 corporate profits rebounded (rising 6.1 percent in the quarter, after falling 2.2 percent in Q1),1 headline and core inflation moderated slightly, and two new regulations (the Inflation Reduction Act, and an executive order to forgive student loans) were signed, aimed at helping companies and households.

But it’s not all sweetness and light. An August survey of CEOs found that 81 percent of leaders expect a recession.2 And while the upward revision in Q2 GDP is welcome, the –0.6 percent reading is precisely in line with McKinsey Global Institute’s downside scenario. The latest report on job openings showed that the labor market remains white hot. While more people are rejoining the workforce, that’s both good and bad news: more workers could ease labor shortages but also create more demand, stoking inflation.3 In addition, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ latest consumer price index indicated that core inflation has increased. For a complete wrap-up of all the US and global economic news, see “Global Economics Intelligence executive summary, August 2022.”

Amid all the uncertainty, one trend has been consistently clear: the US Federal Reserve’s stated commitment to fighting inflation, using the tools at its disposal—higher rates and “quantitative tightening.” As Fed chair Jerome Powell said, the Fed’s “overarching focus right now is to bring inflation back down to our 2 percent goal. Price stability is the responsibility of the Federal Reserve and serves as the bedrock of our economy. Without price stability, the economy does not work for anyone.”4

The clarity and commitment may have reassured some executives. But not all have yet come to terms with the scale of the effort required. It might take years to reduce inflation to the Fed’s target level. Consider these comments from the head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York: “I think inflation expectations are well anchored. We’ve communicated over and over and over again our commitment to achieve that 2 percent goal. . . . Today we’re very clear on that … the situation is very challenging. Inflation is very high. The economy, like I said, has a lot of crosscurrents. I do think it’ll take a few years, but we’re going to get that done.”5

What does that mean for US companies? It’s likely that the private sector is entering a new era of “higher for longer” interest rates and cost of capital. The good news, such as it is, is that higher rates, while unpleasant and potentially painful, are becoming less of an uncertainty and more of a sure thing. Companies need to draw on the proven playbook for success in a world of slower growth, higher inflation, and more expensive capital. That’s a big switch from the activities of the past several months, when many management teams have been putting out fires, so to speak—finding fixes for problems like rapidly rising costs for raw materials and labor. And as Fed chair Powell indicated, it won’t be easy—the switch to a higher-for-longer environment “will bring some pain to consumers and businesses.”6

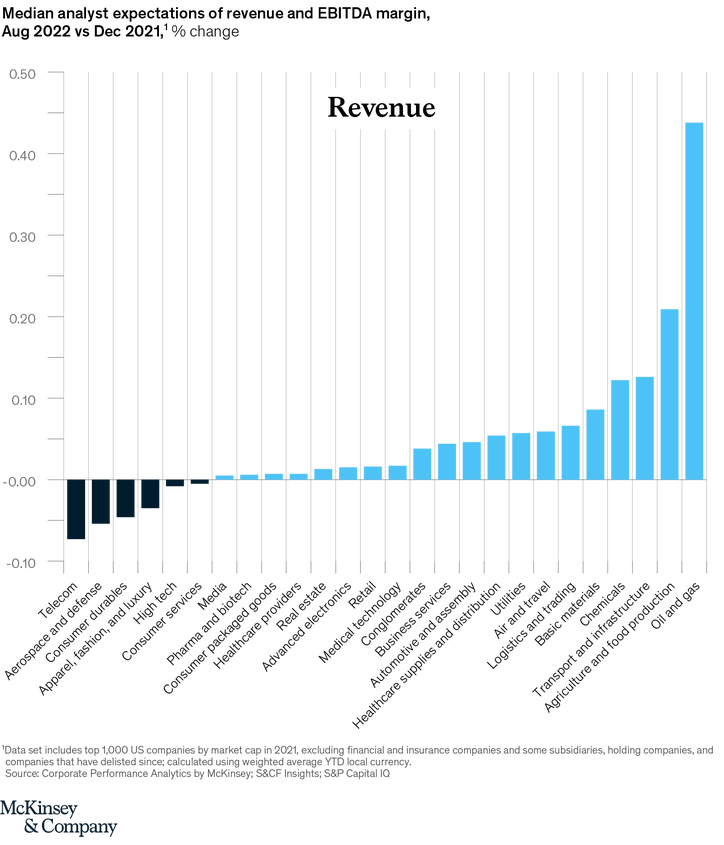

In this update, we’ll look at two new McKinsey research efforts (one on consumers, one on corporates) that point up the ways that consumer behavior is affecting corporate profits and will likely continue to do so. We’ll close with some notes from the field on what we see companies doing today, and four strategies that can help companies thrive in a higher-for-longer world.

Higher for longer: The risk of entrenched inflation

How high, and for how long? Those are quickly becoming the questions of the day. On the first, our recent work with hundreds of US companies suggests that executives should not worry about whether the next rate hike is 75 basis points or something else. It’s the terminal rate that counts, and how long rates remain there, since a quick pivot seems unlikely. Many economists currently expect the Fed’s key lending rate to top out at about 4 percent or slightly higher, which equates to a prime rate of about 7 percent.7

On the second question, history provides some guide. Alan Blinder of Princeton University notes that of 11 rounds of Fed tightening since 1965, one lasted three years, most lasted from one to three years, and only one was over in less than a year.8 All but three resulted in an official recession, and only one qualified as what Blinder calls a perfect soft landing.

The difference between one year and three or four is enormous, of course. The key distinction between a quick resolution and a drawn-out battle is the degree to which inflation has become entrenched in consumers’ and business leaders’ minds. Two new McKinsey research efforts point up the challenges some companies face in a higher-for-longer world.

Consumers: Seeing inflation everywhere

When we surveyed 4,000 US customers in July, they were alarmed at the rapid onset of inflation (Exhibit 1).

It’s no wonder that consumers are somewhat shell-shocked. When we look across the broadest measures of consumer spending on goods and services, we see that inflation is widespread—over the past 12 months, prices have increased in more than 90 percent of categories, a rate of diffusion not seen since the 1970s (Exhibit 2).

Not only does this create challenges on its face, but, as our colleagues identified in their recent consumer survey, consumers’ perceptions of inflation may even exceed the rate of inflation itself. One potential implication of these facts and perceptions is that higher inflation may become entrenched in consumers’ outlooks—precisely the phenomenon that the Federal Reserve seeks to avoid.

All in all, it’s a daunting outlook. Consumer sentiment rose very slightly in August but remains at an all-time low (Exhibit 3).9

Operating in a higher-for-longer world

We’ve seen companies take many of the short-term moves our colleagues outlined in their playbook for inflation. Some of the most common include pricing adjustments and managing exposure to input costs. Some companies are also taking action on operating expenses. These short-term moves can help many companies. But they’re more like firefighting than putting in fire-resistant materials—and in a higher-for-longer environment, companies should also be thinking about more structural solutions that not only manage costs but also build resilience and can drive long-term value creation. Here we offer four themes that business leaders can consider. It’s a complex and difficult program and will require leaders to build new strengths to see it through. But the payoff will be worth the effort and investment.

Growth: Opting in. Growth is always a top priority for C-level executives but remains elusive for many. In fact, about a quarter of companies don’t grow at all, often because leaders don’t look widely for growth opportunities and then hedge their bets, often zeroing in on just a couple of initiatives. Inflation and the rising cost of capital have made it even harder to know where to invest. In an economic moment like this, a structured approach to growth is paramount.

Outperforming executives break the powerful force of inertia by prioritizing growth, a choice that shapes behavior, mindset, risk appetite, and investment decisions across the organization. Intriguingly, our research shows that growth-oriented leaders react decisively to shorter-term disruptions that can be turned into opportunities—what we term “timely jolts”—and build organizational resilience and agility to respond to change and leverage disruption. A higher-for-longer environment is exactly the kind of jolt to growth that leading companies recognize and take advantage of.

Talent: Closing supply-demand gaps. Even in this environment, many companies are still hiring. But our research indicates that talent pools in many industries are drying up as employees quit to enter other sectors, go after nontraditional opportunities such as gig-economy work, or leave the workforce altogether. Shortages of digitally savvy workers are especially acute: in our recent survey, nearly 90 percent of C-suite executives said they don’t have adequate digital skills.

Leading companies are taking several approaches to strengthen their workforces. Many have sought to motivate workers with more meaningful assignments and better opportunities for career advancement. Often, these approaches go hand in hand with training in skills that are hard for companies to find. Some companies are choosing to deemphasize (or discard) requirements for education and relevant experience and hire people from unconventional backgrounds—other industries, adjacent majors, overlooked colleges and universities—who are ready to learn. We’re also seeing businesses streamline their hiring processes and enhance candidate experiences to attract more applicants and lift conversion rates.

Evidence also suggests that improving workers’ emotional experience on the job can do more for retention than employers might expect. McKinsey surveys of managers and employees found that employers often fail to understand just why workers leave their jobs. In particular, employers tend to overrate “transactional” factors such as pay and development and underrate the “relational” elements—a feeling of being valued by managers and the organization, the companionship of trusting teammates, a sense of belonging, a flexible work schedule—that employees say matter most. Companies that successfully create this kind of meaningful purpose can benefit from greater organizational cohesion and resilience.

Sustainability: Staying the course. In a slowing economy, with margins under pressure and the cost of capital sharply higher, should companies invest in sustainability? Our answer is yes. In an economically constrained environment, a through-cycle view on sustainability can be a lever for companies to build resilience, reduce costs, and create value.

Companies in hard-to-abate sectors can protect their core by building resilience against transition risks. Putting an accurate price on the current volatility of fossil fuel prices could make sustainability investments more economical. And transitioning to greener asset and product portfolios can protect against customer attrition as standards continue to tighten. Further, in a slowing economy, a strong sustainability strategy can accelerate growth by creating value. Companies may adjust their business portfolios to capture larger shares of segments with major green growth potential, while others may launch new green businesses altogether. Green products and value propositions may also allow companies to differentiate themselves and gain market share or seek price premiums.

Supply chain: Rebuilding for resilience and efficiency. For many leaders, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed a painful truth about modern approaches to managing supply chains: engineering these vast systems for high efficiency had introduced vulnerabilities. Operational weaknesses such as overreliance on certain suppliers, scant inventories of critical products, and overstretched production networks left companies exposed to shortages and disruptions. Many supply chain leaders declared intentions to make supply chains more resilient, and many did so—though often in the most expedient way possible, by building inventories. Companies can take other, more complex moves to build resilience. For example, our experience suggests that reconfiguring supply networks cut costs by 4 to 8 percent.

Moreover, companies can both build resilience and extract additional savings from already-lean supply chains. We’ve found that a careful assessment of supply chain vulnerabilities can reveal opportunities to lower spending with high-risk suppliers by 40 percent or more. Adjusting transportation modes and routes and distribution footprints around trade tensions, tariffs, possible customs-clearance problems, and likely disruptions can also lower transportation costs by some 25 percent. Then there are the benefits of refreshing products with modular designs that involve easy-to-find components rather than highly customized ones. This can result in margin expansion of 25 percent, while lessening the risks that come with depending on just a few suppliers.

The plot thickens. As contradictory evidence pours in, the US economy remains too tricky to forecast easily. Companies should rely on scenario planning and prepare a set of long-term moves that will help them thrive in a higher-for-longer environment.